In a previous post I described how, at the age of about eight, the Tintin books arrived in my world thanks to the small collection in Mr Kennick’s classroom. Actually, on reflection, I was probably aware of the characters earlier thanks to the Belvision episodes of ‘Hergé’s Adventures of TinTin’ which first aired on the BBC in 1962, when I was four. Watching these back now on YouTube, I’m struck by how, as they were dubbed from the original French into English, the characters have an American, or at least transatlantic accent; not surprising since the voice actors were largely American. But in all it’s manifestations, for my money the screen animations have never been able to completely replicate the charm of the books.

For those who haven’t already explored the Tintin universe, a potted history. Georges Remi was born near Brussels in 1907, and began drawing his comic action strips in 1926; three years later his most famous creation took to the page in his first adventure, Tintin in the Land of the Soviets. The comics would be made into books. Hergé would go on to produce a further 23 books, which would be translated into 70 languages and become a publishing phenomenon. The character would become the star of television series, of movies, and today is an icon of marketing.

“Tintin in the Land of The Soviets’ has had an unusual life. Drawn when Remy was only 21, it clearly displays the extreme anti-Bolshevik stance of the comic which commissioned it, La Vingtième Siécle, alongside the crude cartoon-style of the drawings. The characters are little more than stereotypes, with the Russians portrayed as Soviet Commissars, Bolshevik anarchists, or OGPU policemen. Tintin‘s adventure has to take place without any of the later staple characters – he’s alone except for Snowy. And he manages to fight and battle his way through an army of dastardly Soviet villains, in the effort to show readers that these opponents are little more than thugs and bullies, no match for the eponymous Belgian hero; the story also makes clear that the oppressive Soviet treatment of their citizens (not entirely fictional at all) was likewise no cultural match for civilised Western European nations such as Belgium.

Of course, La Vingtième Siécle was firmly in the French and Belgian tradition of Catholic Conservatism, so ‘TinTin in the Land of The Soviets’ was largely a propaganda exercise, and as such was accompanied by a huge publicity campaign, including an enactment of Tintin arriving from Moscow with a little white dog, on the appropriate express at Brussel’s Gare du Nord station to cheering crowds, followed by a motorcade and a speech at the newspaper’s offices.

The action can only be framed in a wholly cartoonish world, and is a repetition of Tintin fighting the bad guys and using a series of planes, cars and even a diving suit to evade capture. These encounters are as crude as the drawings at this stage, and the whole enterprise is cast as little more than a way to emphasise the anti-Soviet message. But this story needs to be seen in the context of the time, recognising the fact it was an embryonic depiction of Tintin – consider how much the later stories benefited from lacing the central character of Tintin amongst a wider cast of regular figures.

One figure who comes out almost fully formed and remains so throughout in both character and drawn form is Snowy. Already, he’s rescuing Tintin, getting into slapstick scrapes, and having conversations with himself. But Tintin would undergo some development before he became the recognisable ‘boy reporter’. Consider these images, first from ‘Land of The Soviets’, and then from the final book, ‘TinTin and The Picaros’:

“Land of The Soviets’ had as its central theme Soviet treatment of the peasantry, which mirrored the real-life assault on wealthier peasants in the Soviet Union known as ‘dekulakization’. Unfortunately, this political attack on Bolshevism suffers badly from the clumsy and repetitive action, and this smothers any serious points it could have made.

Of course it needs to be recognised that these were initially comic strips, in a children’s comic. In fact throughout it’s life, ’The Adventures of Tintin’ appeared in both strip and book form. But since the earlier stories needed to conform to comic strip parameters, then ‘Land of The Soviets” hurtles on at a breakneck speed, without time for plot- or character-development. You can see this in the way that the final frame of each second page usually has some kind of disaster, or a car crash, or Tintin being captured, as a way to keep the readers excited for the ‘next thrilling instalment’, as they used to say.

The first three books, ‘In the Land of The Soviets’, ‘TinTin in the Congo’ and ‘TinTin in America’ show a distinct progression in terms of drawing and development of the characters. ‘Tintin in the Congo’ is one of the most problematic of the entire canon. Its depiction of Africans would later be held up as an example of the racism of Tintin, and through him Hergé, often without the necessary context. (In fact, it took English publishers until 1991 before they would publish, down to it’s racist depictions.)

That context is Belgian colonialist adventurism in Africa. And although Belgian colonialism provides the background, the depictions, paternalism and racist tones would easily strike a clear chord in all other western readers of the time. But the book, as did others, underwent significant changes as later editions responded to changing attitudes, the availability of colour, and less pressure from the publishers to propagandise a particular political viewpoint. For instance, the character of Jimmy MacDuff is transformed from a crude stereotype into a much more realistic-looking white man, in the redrawn version of 1946. (It strikes me that even then, Hergé didn’t wish to take the trouble to depict the remaining black people in a normal way. Or was he influenced by his racist publishers to show the savages as they wished the readers to see them? Another likelihood is that racism in white Europeoan culture was by now so embedded and pervasive, that this was the normality of illustrating or describing black people – as savages, as ignorant, as ridiculous, but always as inferior. But I must be careful here, or I’ll be back on one of my soap-boxes, the one marked ’white bigotry’…)

By the time of the third book, where our hero finds himself in America, the characters of Tintin and Snowy have settled into a more recognisable style; although the influence of the anti-Soviet, anti-capitalist Belgian Catholic Right is still seen in the depiction of Tintin battling gangsters, and encountering Native Indians. But it includes the wry and sardonic humour which Hergé was increasingly using – for instance, the frame which shows Snowy’s cell after he’s been abducted by gangsters, has a sign on the wall which reads ‘Kidnap Inc – Rules for Guests’. The book runs the gamut from skyscrapers and machine guns to Teepees and warbonnets; Hergé wanted to write about the ‘Red Indians’ of the stories he’d loved as a boy, but the pressures from his publisher made him depict American society as crime-ridden and violent, presumably to show again how much more civilised Belgian Catholic/Conservative attitudes were to those Americans. (My, how the Free State Congolese must have chuckled…)

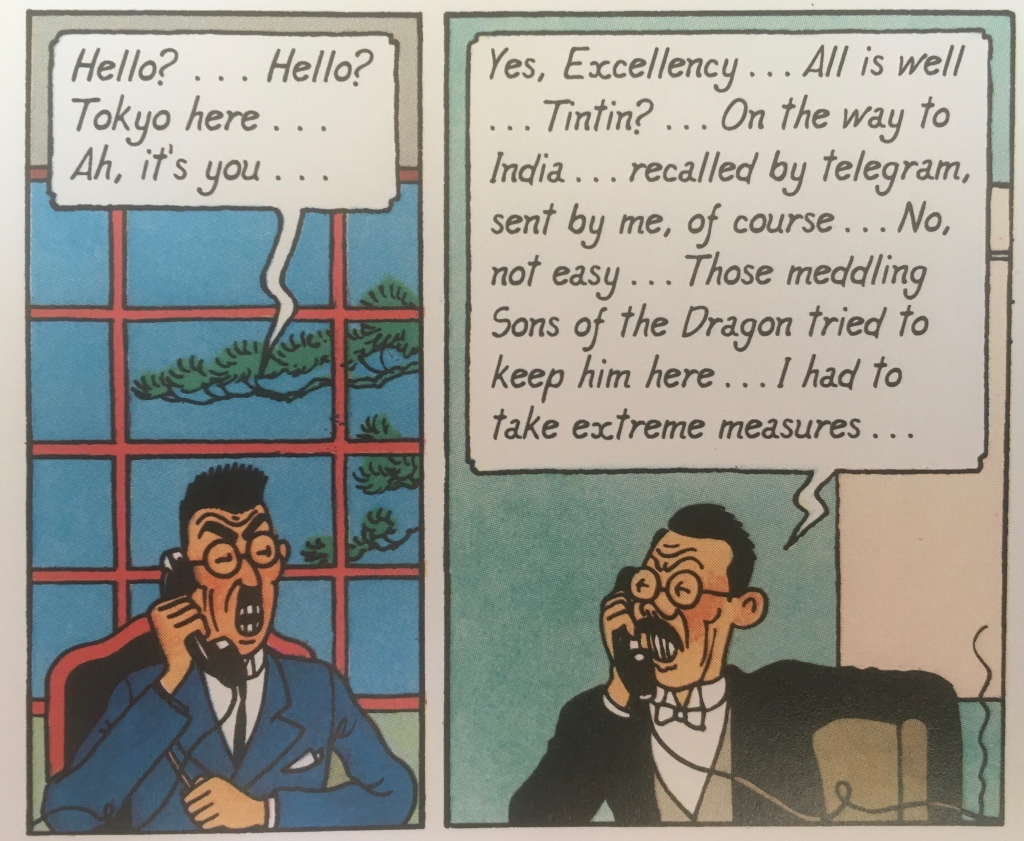

By the time of the fifth story, The Blue Lotus, Hergé is really getting into his stride, although he still uses very crude depictions of antagonists – note the way the Japanese are shown.

It’s plain that whilst Hergé still uses stereotyping, by now, thanks to his increasing fame and independence from outside influences, he’s able to concentrate more on plot development, and depict world events in a much more rounded way. The Blue Lotus, for instance, uses as it’s backdrop the Sino-Japanese War and Japanese militaristic ambitions . Having been prevailed upon to avoid Fu-Manchu style characterisations of the Chinese, and the influence of Zhang Chongren, a Chinese friend Hergé had made and who was to awaken a deep interest in the China and its people, this story saved all its negative depictions for the aggressive Japanese.

There’s a new maturity in this story, and Hergé seems to be moving further away from his traditional Belgian upbringing in it’s colonialist, Catholic right-wing structures, and to a more rounded, almost left-wing viewpoint of Nationalism, militarism and racist depictions.

The Blue Lotus, published in 1936, would herald a change in style and approach; the next three books -The Broken Ear, The Black Island, and King Ottokar’s Sceptre – would take Hergé and Tintin right up to the edge of Nazi invasion and World War 2. So, as Hergé might say, in the next thrilling instalment…

Leave a comment